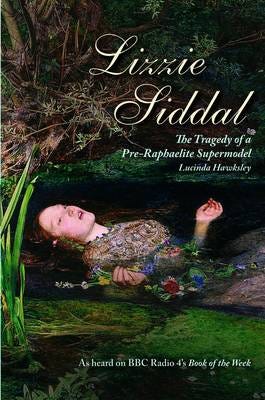

What follows is an excerpt from the beginning of my first biography, of the artist and Pre-Raphaelite model Elizabeth ‘Lizzie’ Siddal, a woman whose role as an artist’s model helped to changed the perception of female beauty. My book, Lizzie Siddal, The Tragedy of a Pre-Raphaelite Supermodel, is available to buy in all good bookshops and online. [1] The American version was entitled Face of the Pre-Raphaelites.

Chapter 1

In mid-nineteenth century London, if you wanted to buy a hat, you would have made your way to the area around Leicester Square. The narrow thoroughfares that were Cranbourne Street, Cranbourne Alley and Cranbourne Passage were the places to go, crammed with milliners, mantle makers and dressmakers. The streets were so slender, the shops so numerous and the roads so crowded, that it was difficult to pass along them unimpeded. Any lady naïve enough to find herself in this district while wearing an unfashionable bonnet or cloak would be swamped by overwhelming offers of assistance and numerous entreaties to buy a new one, often accompanied by tussles over the potential customer by rival shops’ assistants. There were incidences of women having their clothes ripped or even of being temporarily ‘kidnapped’ by over-eager salesgirls, who would seize the witless wanderer and hurry her into their shop before any rival snapped her up. In the late 1840s, number three Cranbourne Street was a hat shop, owned by a Mrs Mary Tozer. To help her in the business, Mrs Tozer employed several attractive girls and women, who not only made the hats and worked as shop assistants, but could also model the headgear to its best advantage. One of these was a young woman named Elizabeth, or ‘Lizzie’, Siddall[2].

In 1849, Lizzie was twenty years old and had lived an unremarkable life. She was tall and slender with large eyes and long hair the colour of pale copper. Striking, rather than beautiful, especially with those huge, heavy lidded eyes in such a small face, Lizzie did not conform to the contemporary ideal of beauty. Her greatest considered attributes at this date, were that she had perfect deportment, fine facial bone structure and was unusual looking. A woman one would look at and remember. By fashionable dictates, however, she was too tall, not womanly because not curvaceous and her hair was red – most definitely not considered an attribute. Superstition still deemed that red hair was unlucky and associated it with witches, black magic and a biblical reference to Judas Iscariot having red hair. Although the educated classes would have scoffed at such a notion of a hair colour being unlucky, there was a far larger number of uneducated people in Britain, who continued to believe red hair was something to be shunned and to be afraid of. The poet Algernon Swinburne (1837–1909), who was to become one of Lizzie’s most devoted friends, had hair of almost identical colour to hers. He related stories of how, when he was a child, the people in his local village had regular forays to throw stones at red squirrels, as their coppery fur was believed to be the cause of bad luck. Common folklore dictated it was unlucky if the first person you saw in the morning was a redhead, particularly a woman with red hair. Shipping superstition decreed that redheads brought bad luck to a ship (so, apparently, did flat-footed people); if a sailor could not avoid making a voyage with a redhead, he was warned he must speak to the red-haired person before that unpropitious being uttered even a syllable to him, in order to reverse the bad luck.

These superstitions sound ridiculous today, but they were long-lived and deep-seated: the belief that red hair is unlucky dates back to the Egyptians, who burned redheaded women alive in an attempt to wipe them all out. Queen Elizabeth I finally made red hair popular in England, and stopped the English persecution of redheads for being witches or warlocks, but even three hundred years after Elizabeth’s reign, other prejudices against red hair remained amongst the ignorant. Throughout her childhood and adolescence, Lizzie often suffered teasing for the hair that was destined to become her greatest feature.[3]

Mrs Tozer’s employees worked long hours and in tiring conditions. Although the shop itself had a large display window, so potential customers could see the hats, the working area where these were created was badly lit, with just one small window that looked out to the back of the building on a scrubby patch of mud and grass. The girls would start work early in the morning and usually continue until 8pm. During especially busy times, such as the London Season, their hours would be extended and they could sometimes work all night. Lizzie, who lived in Southwark, often walked home from work with a colleague named Jeanette, who also lived south of the river. The girls were not particularly close friends, but it was not safe to be on one’s own in the dark, so the company of someone else was necessary, as well as welcome on such a long walk.

Little is known of Jeanette except that she had a host of admirers, including the Irish poet William Allingham (1824–89)[4]. At the end of 1849 Allingham was working as a Customs Officer, but had finished his first volume of poetry, had had it accepted and was waiting for it to be published. He did not live in London, but made frequent visits, both on business and to see friends. These friends included the recently formed Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and their circle; in particular, the promising young artist Walter Howell Deverell (1827–54). When Allingham made his visit to London in the winter of 1849–1850, he found his friend struggling with a painting he wanted to exhibit at the Royal Academy. It was of a scene from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night and Deverell was desperately seeking a model for Viola. In the end, it was Allingham who found the solution to his friend’s problem, and that was quite by chance. Being in London, he decided to visit Jeanette and offer to walk her home from work. They were accompanied by a tall, silent workmate, Lizzie Siddall.

Allingham was not initially overly impressed by the redheaded girl, finding her ‘stuck up’ and dull; although he was presumably somewhat prejudiced against her for her unintentional intrusion on his intended romantic walk. Despite this unpropitious start, Lizzie and Allingham went on to become good friends. After her death, Allingham wrote that ‘She was sweet, gentle and kindly, and sympathetic to art and poetry .... Her pale face, abundant red hair and long, thin limbs were strange and affecting, never beautiful in my eyes.’ At this first meeting, however, he did know she would be perfect as Deverell’s model, not least because she was so slim. Deverell wanted to paint Viola in boy’s clothing and was despairing of finding a woman without prominent curves; he had also hoped to find a red haired model[5]. He was painting the episode when Viola disguises herself as Cesario, Duke Orsino’s page boy, and he needed a woman who would look plausible in a pair of breeches.

After being told about Lizzie, Deverell made a visit to Cranbourne Street – one hopes he had the foresight to wear a fashionable hat – to observe Lizzie through the display window. He was thrilled by her and agreed wholeheartedly that Allingham had discovered a genuine ‘Stunner’ (the Rossettian word for any beautiful woman and a term quickly adopted by all the Pre-Raphaelites). It was out of the question for Deverell to approach an unknown young woman himself, so he asked his indulgent mother to talk to Lizzie on his behalf.

Mrs Deverell visited Mrs Tozer’s shop, accompanied by her son, and promptly introduced herself and Walter to Lizzie, voicing his request in the most tactful manner possible. It was a shock to this previously unfêted young woman to be singled out and offered quite bluntly such a very unusual proposition. Although deeply flattered, Lizzie was wary of the offer and uncertain of exactly what it entailed – in the 1840s modelling for an artist was perceived as being synonymous with prostitution and Lizzie’s upbringing had been strictly religious. Modelling was not something any respectable woman thought of doing, unless either related to the artist or sitting for one’s elegant portrait, yet Walter’s mother carried her audience beyond this very understandable prejudice and into an entirely favourable frame of mind; she seemed, indeed, unaware that there could be even the vaguest of reasons to demur, so, in the end, they did not. Mrs Deverell’s very obvious respectability and her reassurances of propriety at all times allowed her to convince both Lizzie and the more worldly wise Mrs Tozer to agree to the proposition. Walter’s indomitable mother then set out to an entirely different part of London from the one she inhabited; to visit Lizzie’s equally formidable mother in the Old Kent Road….

[1] https://www.waterstones.com/book/lizzie-siddal/lucinda-hawksley/9781802797923

[2] She changed the spelling to Siddal a few years later.

[3] Mary Howitt, a Victorian writer who contributed articles to magazines aimed at young women, made the sarcastic comment that the Pre-Raphaelites had ushered in an age in which ‘plain women’ could be considered beautiful. She added that the painters had made ‘certain types of face and figure once literally hated, actually the fashion. Red hair – once to say a woman had red hair was social assassination – is the rage.’

[4] Allingham is best known today for his poem, ‘The Fairies’, which begins: ‘Up the airy mountain / Down the rushy glen, / We daren't go a-hunting, / For fear of little men…’

[5] In wanting a redhaired model, Deverell was following Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s example. The previous year, Rossetti had sought in vain for a redhaired girl to be painted as the Virgin Mary, but had ended up using his sister, Christina, and painting her brown hair as auburn.